THE TURNED ROOM

2023

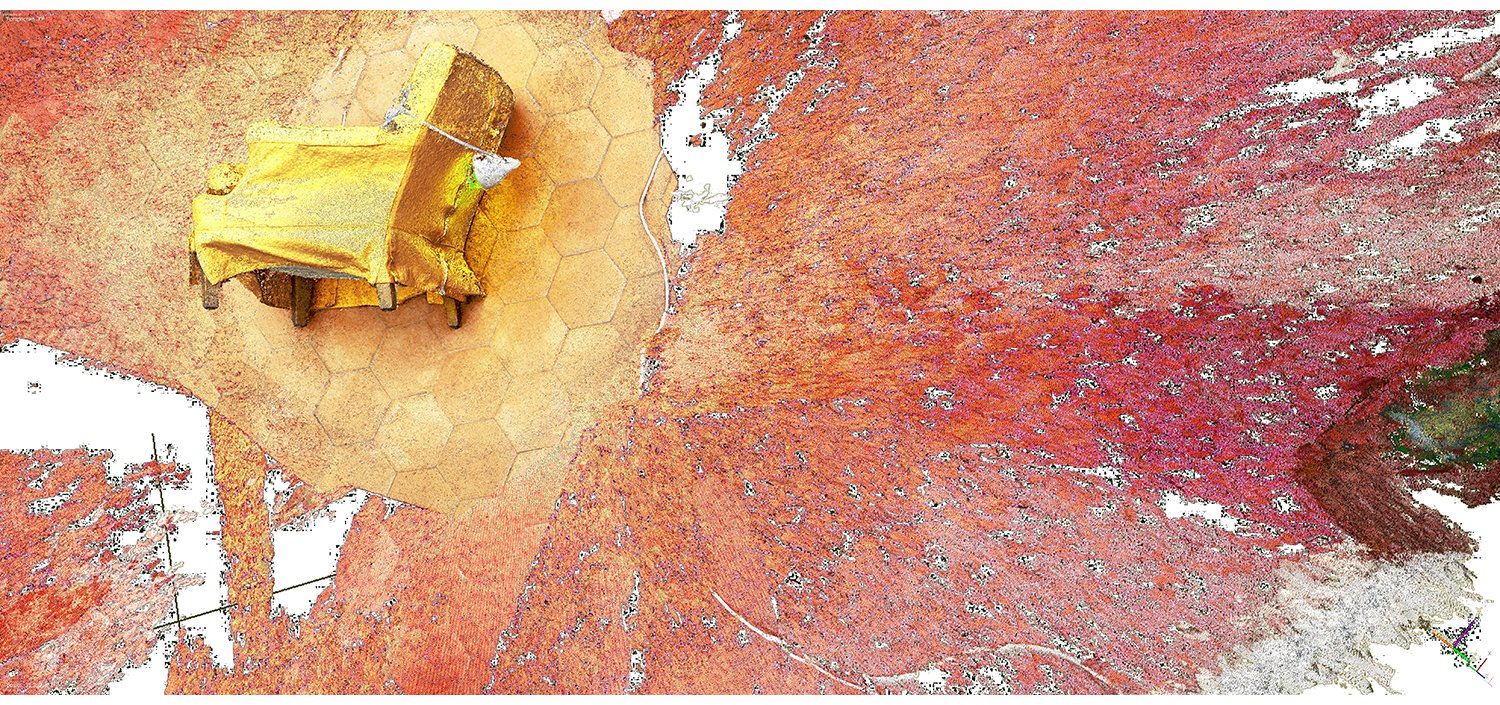

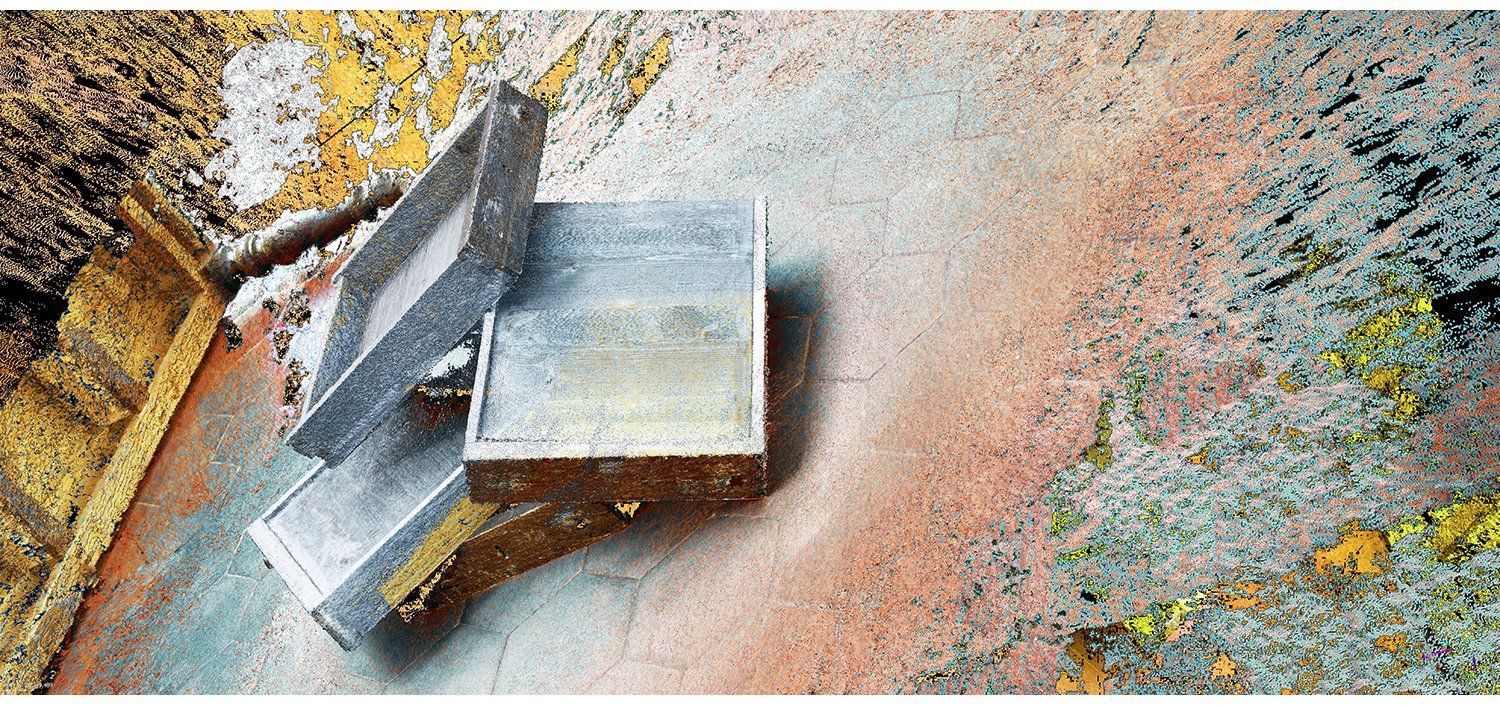

From May 13th to June 16th, 2023, Michael had the honor of occupying the Philip Guston Studio at the American Academy in Rome. Over the course of four weeks, he undertook an experiment in representation specifically constrained by this time and place. Everything worked on was already in the room; nothing could be brought in or removed. The technical processes used for representation were three-dimensional photogrammetry models. The data points of the room were gathered through digital images captured with an iPhone. The captures were a sequence of 15–40 images taken as a series of still frames moving around an object. Each week, a different object—a chair, a phone, a desk, a series of drawers—was positioned on the floor in the space as an object of focus. These objects allowed the background of the room to be captured with relative gradations, from highly detailed to loosely defined, a shift in resolution from realism to abstraction. The weeklong setup also allowed me to capture the room at different times of day, with different qualities of light from different directions, and with different spectrums of color hue. The models consisted of points and only points, averaging around 25 million per model. Selected views of the point-cloud models were extracted at three different resolutions and overlayed as color field studies to develop a specific mood and palate. The proportions of the prints are the proportions of the room. Each object was also turned in relation to gravity, creating—when modeled three dimensionally and viewed from multiple angles—an ambiguity around what was turned: the object, the model, or the room.

Digital sensing and imaging can be defined as the translation of detected environmental energy into numeric information—which is to say, sensing and imaging become interchangeable. The differences between a two-dimensional image and a three-dimensional model, or a still photograph and animate cinema, also tend to blur. The moved image—two images of an object from two different locations—can be sequenced to create a sensation of camera motion, but these displaced images can also be used to triangulate the location of a point in space, as with humans’ binocular vision or when birds bob their heads. This moved, or doubled, image of the world is also the basis of photogrammetry. Used in surveying for centuries, the doubled image—“a point in space known through two interrelated projections”—is the fundamental principle of Gaspard Monge’s Descriptive Geometry (1798), which was the foundational course of the École Polytechnique; it is also the technical basis of interrelated plans and sections in architectural drawing.

Photogrammetry models approximate the location and color of a point in space from multiple images of the point. No hierarchical difference between an object and its context is predetermined; everything in the environment becomes evenly captured energetic data, a homogeneous field of colored marks in a matrix, sometimes appearing abstract, at other times, realistic. These patterns of hue values appear at different densities depending on the resolution of the initial images and the confidence the software has in triangulating spatial location. Another way to say this is that there are no figures determined by a contoured edge, only grounds of variable hue, saturation, and brightness. Spatial depth is a computational displacement created by approximation from local regions of color pattern difference.

Questions of variable resolution of mark making, color patterns, figure/ground, and realism/abstraction, seem to be old aesthetic issues typically related to “formalism” within late 19th and early 20th century art theory. But with the current use of these scanning technologies and photogrammetry models, these exact same issues have mutated into a different set of valuations for a multitude of disciplines and interested agencies, including, to list a few: petroleum extraction, climate change studies, underwater exploration, military targeting operations, weather simulations, forensic reconstructions, police surveillance, fauna-migration tracking, autonomous vehicle navigation, agricultural management, and advertising campaigns. What remains is for architects to articulate a working space within an imaging technology that hovers between observation and speculation, with representations that are rendered as realism from the drop, and with space conditioned by the fluctuation of background energy. These experiments from The Turned Room offer no conclusions, they only posit starting points, and more questions.

© All content © Young & Ayata